How Does Farm Animal Welfare Affect Agriculture .edu

Costs and Benefits of Improving Farm Animal Welfare

one

The Queensland Alliance for Agriculture and Food Innovation, The Academy of Queensland, St Lucia, QLD 4067, Australia

2

The Animal Welfare Collaborative, The University of Queensland, St Lucia, QLD 4067, Australia

three

Animal Welfare Scientific discipline Eye, Faculty of Veterinary and Agricultural Sciences, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC 3052, Commonwealth of australia

*

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

Bookish Editor: Elske North. de Haas

Received: 30 December 2020 / Revised: xix Jan 2021 / Accustomed: 22 Jan 2021 / Published: 27 January 2021

Abstract

It costs coin to improve the welfare of farm animals. For people with animals nether their care, there are many factors to consider regarding changes in practice to meliorate welfare, and the optimal course of action is not always obvious. Decision support systems for fauna welfare, such as economical toll–benefit analyses, are defective. This review attempts to provide clarity around the costs and benefits of improving subcontract brute welfare, thereby enabling the people with animals nether their intendance to make informed decisions. Many of the costs are obvious. For example, training of stockpeople, reconfiguration of pens, and assistants of pain relief tin improve welfare, and all incur costs. Other costs are less obvious. For case, in that location may be substantial risks to market protection, consumer acceptance, and social licence to farm associated with non ensuring good animate being welfare. The benefits of improving subcontract animal welfare are besides difficult to evaluate from a purely economic perspective. Although it is widely recognised that animals with poor welfare are unlikely to produce at optimal levels, there may be benefits of improving animal welfare that extend across product gains. These include benefits to the animal, positive effects on the workforce, competitive advantage for businesses, mitigation of run a risk, and positive social consequences. We summarise these considerations into a determination tool that can assist people with farm animals nether their care, and we highlight the need for further empirical prove to ameliorate decision-making in animal welfare.

1. Introduction

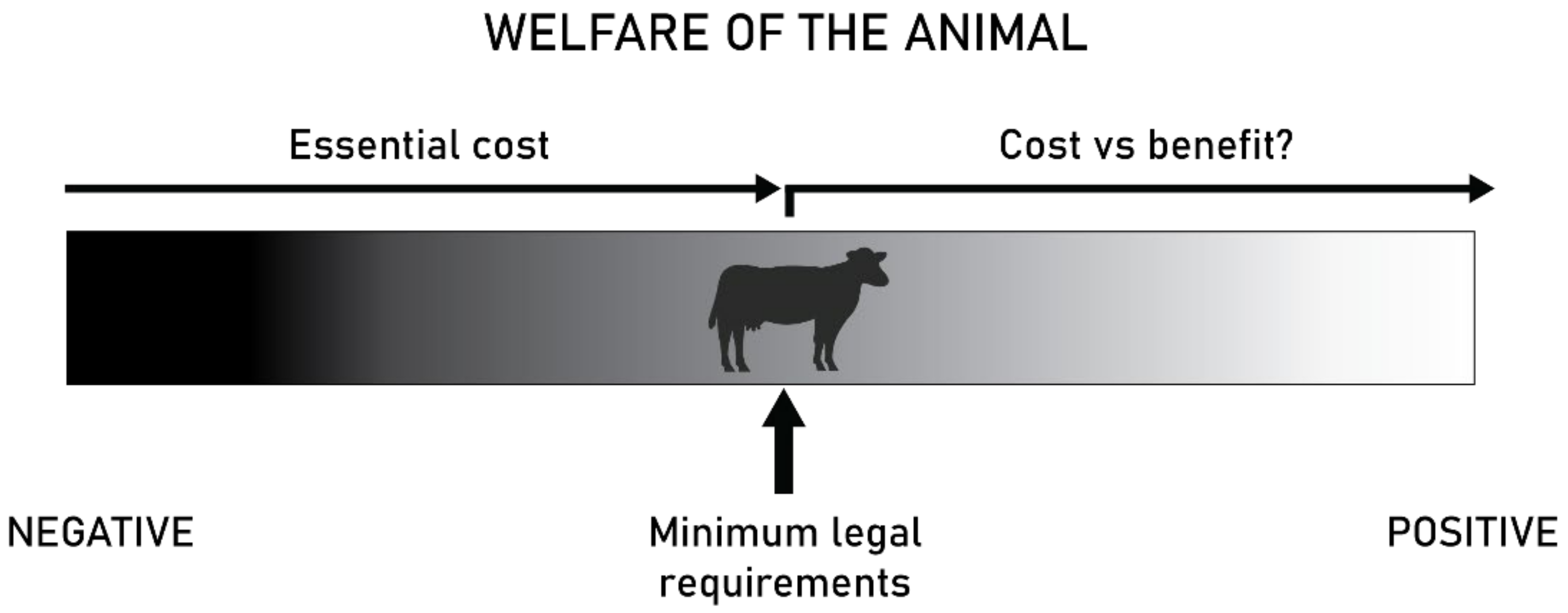

Animal welfare is of increasing concern to society, and many people with farm animals under their care, such as farmers, stockpeople, truck drivers, and butchery (slaughter-house) workers, are striving to improve the welfare of those animals. Since the Brambell Committee established past the British Government outlined the 5 aspects of beast welfare nether human command in 1965, giving rise to the "five freedoms" framework [1], various other frameworks have been developed to assess brute welfare [2,3]. For the purposes of this review, we define animal welfare every bit a transient state within an creature that relates to what the creature experiences. This definition builds upon the definitions of animal welfare put forth by the Globe Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) and the French Bureau for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health and Safety (ANSES) and builds on the work of Mellor, Patterson-Kane, and Stafford [4,5,6]. Irrespective of which definition one may apply to appraise fauna welfare, it is important to admit that there is a continuum of welfare for animals, ranging from negative to positive (Figure 1). Improving animal welfare means ensuring that the experiences of the animal are as positive as they possibly can be, which often requires changes to infrastructure and practices by the people responsible for the care and handling of the animals.

Despite their desire to meliorate the welfare of farm animals, those with animals nether their care may be prevented from taking activeness considering of the complexity of deciding which practices to improve and past how much. There are many factors for them to consider, including costs associated with changing practices, possible benefits to the animal, projected benefits to the business concern, and other less tangible implications for society. On the other hand, there may also exist a cost associated with not improving fauna welfare. The costs and benefits of improving farm creature welfare are not always obvious. Considerable endeavor towards understanding the economical value of improving beast welfare has come from the works of John McInerney, who said that the question is not what the improvement in animate being welfare costs, but what information technology is worth and, importantly, whether this sufficiently exceeds the cost, making information technology a adept affair to practice [seven]. In this review, nosotros endeavour to further clarify the costs and benefits associated with improving farm animal welfare, with the view that this may enable people with animals nether their care to make informed decisions.

2. The Cost of Doing Nada

When it comes to addressing farm animal welfare, possibly the easiest selection is to do nothing at all, but in that location may be a cost associated with doing zilch. This cost comes in the grade of a chance. Public concern well-nigh subcontract creature welfare has been researched over a considerable period [8,9,x,11,12,13], and in that location is some prove to indicate that public concern is growing [eight,xi]. The risk to those with farm animals nether their intendance is that if they do not adequately address the public's concerns near the welfare of the animals, their correct to ain and apply the animals for their commercial purposes may come up into question.

This "…latitude that lodge allows to its citizens to exploit resources for their private purposes" is what Martin, Shepheard, and Williams (2011, p. iv) refer to as social licence [14]. Social licence is granted when industries conduct in a manner that is consequent, not merely with their legal obligations, merely also with community expectations [fifteen,16,17]. Animal welfare issues, together with issues relating to climate change, water scarcity, and failing biodiversity, accept all been recognised as potential threats to a farmer'south social licence to operate, but some argue that animal welfare has recently get the most crucial consideration underpinning social licence for Australian brute use industries [18].

There are few economic estimates of the chance of losing social licence to operate in the farming sector. In 2015, the Australian cerise meat industries estimated that the downside risk of not maintaining consumer and community support for the industries would event in a potential accumulated loss of AUD 3.ix billion (USD three.0 billion) by 2030 [19]. Addressing public concern over animal welfare was identified as the major component of maintaining consumer and customs support. This loss is compared with potential gains in productivity resulting in AUD 0.22 billion (USD 0.17 billion) to the industry [19].

To know whether social licence is in fact being lost, it may be useful to measure a more tangible parameter, such every bit public trust in the farming sector. Coleman et al. (2019) investigated the appointment of the Australian customs in a range of behaviours to limited opposition to the livestock industries. These oppositional behaviours included actions that required relatively little investment of effort, such as talking to family unit, colleagues, and friends, and those that required greater investment, such every bit writing to a politician, calling talk-back radio, or altruistic money to a welfare organisation. When comparing these behaviours between 2013 and 2019, most oppositional behaviours, particularly those that required some effort, increased in prevalence. Furthermore, the more oppositional activities that were undertaken, the greater the mistrust tended to exist, with the correlation growing stronger betwixt 2013 and 2019. For example, the correlation between these oppositional behaviours and "trust in people involved in the Australian livestock industries" changed from −0.37 to −0.44. [20]. These survey findings point that trust in the Australian livestock industries may be on the reject. Public attitudes around farm animate being welfare are certainly shifting, but the extent to which these changes in attitude are having an economic touch on on the industries that rely on farm animals is still unknown.

Even if livestock industries do not lose public trust more often than not, specific welfare issues can enhance concern with other stakeholders who have an influence on the supply chain. Public attitudes to specific livestock husbandry practices, such every bit beak trimming, tail docking, and castration, are more often than not negative [21], and targeted awareness campaigns can heighten the profile of an result to such an extent that is has an touch on on an industry. For example, near half of Australian wool farmers surveyed in 2011 believed that consumers did not care almost the result of mulesing [22], a practice that involves cutting crescent-shaped flaps of skin from effectually a lamb'south breech and tail such that when it heals, it creates an area of bare scar tissue with no folds or wrinkles, making the animal less susceptible to flystrike [23]. Farmers' beliefs most mulesing were consistent with a public attitudes survey in 2000, which found that Australians' disapproval of mulesing was depression (three%) [12]. Yet, a widespread media campaign in 2004 by People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) prompted certain strange buyers to boycott the buy of Australian wool [24,25], and past 2006, Australians' disapproval of mulesing had grown to 39% [26]. Similarly, infinite allowance for farm animals has been the discipline of significant adverse media coverage. For example, the Viva! "Happy Eggs" investigation in Corking Britain in 2016 against caged hens led to widespread media coverage targeting enriched cages [27]. A similar campaign in Commonwealth of australia against sow stalls, the 2014 "Save Infant" campaign by Animals Australia, led directly to industry changes, whereby the revised Australian Code of Do at present includes changes to the duration that gestating sows can be housed in stalls [12].

Another manner in which trends in public business concern about subcontract animal welfare can apace affect industries that rely on farm animals is through government action. Adverse media coverage, for instance filming of desperately compromised sheep welfare and mortality during live beast ocean ship from Australia to the Middle East and filming of housing conditions past animal welfare groups [28], can pb to expressions of public business organization that subside fairly rapidly. Even though the issue of these episodes on public attitudes is oft short lived, governments may react to these expressions of public concern with such speed that it may non give the livestock industries much time to adapt. In that location have been numerous examples where extensive media coverage of animal mistreatment has led to widespread community discussion; demands by retailers for suppliers to satisfy welfare audits; and, in at least 1 case, firsthand regime intervention [12]. There is as well bear witness that failure to maintain social license can lead to increased litigation, increased regulations, and increasing consumer demands, all of which hamper the success of industries [15].

Interestingly, there is some evidence that all-encompassing publicity of an adverse effect may not have an immediate impact on public attitudes [29]. In this example, there was an Australian media campaign exposing animal cruelty in alive export of sheep by ocean. Attitudes to red meat farming, acceptability of the red meat manufacture, and trust in farmers in the red meat industry were assessed earlier and later on this campaign and did not change. However, information technology is not known whether repeated campaigns of this kind would take an incremental outcome over time on community attitudes and behaviour. According to Martin, Shepheard, and Williams (2011), working with the community, agreement their opinions towards of import problems such as animal welfare and the environment, and cooperating rather than working against them in a defensive manner are the most successful means of addressing threats to social licence [fourteen].

3. Costs of Improving Farm Animal Welfare

Many people assume that if there is a adventure to social licence, those with farm animals nether their care should undertake any necessary changes to their businesses to meliorate the welfare of the animals. In that location are costs associated with these changes, nevertheless. Some of the costs are 1-time costs associated with irresolute infrastructure and switching practices, some are ongoing operational costs, and some are costs to which all businesses in an industry must contribute indirectly. All of these costs are likely important factors in the decision about which improvements should be fabricated.

One-fourth dimension costs associated with improving farm animal welfare tin exist significant, especially if major changes to infrastructure are required. For instance, when the Australian pork industry chose to voluntarily phase out sow stalls by 2017, the reconfiguration of infrastructure to accommodate group housing and manage aggression of significant sows in pork production facilities was estimated to toll the industry AUD 50–95 1000000 (USD 38–73 million) [30,31]. Another example is the decision of some cattle feedlots to install shade infrastructure to reduce the intensity of the heat load experienced by the cattle. In 2011, Sullivan et al. found that price of shade material plus structural back up and fittings was AUD 59.75 (USD 45.99) for 2.0 chiliad2 (21.5 ft2) of shade per animal and AUD 69.74 (USD 53.68) for 4.7 thou2 (l.six ft2) of shade per animal [32]. On the footing of these figures, a technical services officer from the Australian beefiness industry compared the do good of improvements to feed intake and carcass weight relative to cost of installing shades in feedlots. He determined that on the basis of a AUD 450/tonne (USD 314/ton) diet at AUD 3.05/kg (USD 1.07/lb) feeder cattle price, and AUD 6.x (USD 4.69) forward contract price, feeding cattle nether shade over summertime would outcome in at to the lowest degree a AUD xx/head (USD 15.39/head) increase in profit, not taking into account any oestrus-induced mortality or morbidity [33]. Purchase and configuration of technologies to monitor animals (due east.thousand., digital agronomics) is another case of an infrastructure cost. Autonomously from infrastructure costs, changes in practise to amend farm animal welfare frequently require boosted grooming of personnel. For instance, the use of cognitive behavioural preparation, which involves targeting cardinal attitudes and behaviour of stockpeople, has been institute to reduce fear and increase productivity in dairy cattle and pigs [34,35,36]. Given that the costs associated with changes in infrastructure and staff grooming can be meaning, access to majuscule is an of import consideration in improving farm brute welfare.

Even after changes to infrastructure take been made and staff take been trained, at that place may be ongoing costs associated with improvements to farm animal welfare. For example, any intervention to ameliorate fauna welfare that could have a negative effect on production (e.g., slower weight gain or increased time during routine handling or at slaughter) would equate to an ongoing cost to the business. Some interventions to improve farm beast welfare may require ongoing additional personnel, and at that place may be ongoing costs associated with supplies, such as the purchase of hurting relief or enrichment materials, or additional veterinary expertise. These ongoing costs must all be incorporated into the cost of the product, and thus they must ultimately be financed by consumers.

Where there are gaps in knowledge about farm fauna welfare, investment in research, development, and extension of knowledge is required. On an international calibration, much of this investment comes from taxpayers. Many governments invest in research to better the agricultural industries of their respective countries, and some of this investment may go into research to better animate being welfare. In improver, the industries themselves may contribute to inquiry funding through levies imposed on their sales, as is the example in Commonwealth of australia [37]. Therefore, costs associated with research, development, and extension stand for an ongoing indirect toll to businesses with subcontract animals under their intendance. For example, the Australian wool industry has invested in alternatives to mulesing, such as suitable analgesics and genetic research to develop sheep that are less susceptible to flystrike. The current breech flystrike strategy published by Australian Wool Innovation (AWI) says in its preamble, "The Breech Flystrike Strategy provides management for AWI investment in sound, scientific solutions for the direction of breech flystrike to improve lifetime brute welfare, address supply chain expectations and increment the demand for Australian wool" [38]. In Australia, research and evolution corporations such as AWI are funded through a combination of manufacture levies and taxes [39].

Given the costs involved with improving the welfare of farm animals, there are trade-offs for businesses to consider. Those with animals under their care are frequently in a position in which they must appraise whether these costs will exist offset by any potential benefits resulting from improvements to animal welfare. These benefits are often less certain than the costs, however, and tin can exist more than hard to assess in financial terms.

4. Benefits of Improving Farm Animal Welfare

4.1. Benefits to the Brute

Before considering any benefits to the business that result from a change in infrastructure or practices, it is important to consider whether the creature is in fact benefitting from these changes. The benefits will likely manifest in the animate being'due south physiological and behavioural functioning, although these may non always be obvious. Behavioural changes in the animal are the most readily assessed indicators of welfare, whether past direct observation or with the assistance of monitoring technologies. Although rigorous experimental approaches to evaluate behaviour exist, ultimately those with animals under their care (or lodge at large) must brand a value judgement well-nigh whether the observed behavioural changes are desirable or not, and therefore whether they can be considered "improvements". Some behavioural changes accept been correlated with physiological changes in the animal, giving further back up to the interpretation that welfare has improved. For case, specific forms of human contact appear to elicit positive emotional responses in animals. Stroking the ventral region of the neck of dairy cattle has been shown to reduce the heart rate and results in relaxed body postures and increased approach to humans in cattle [40,41,42,43], while stroking combined with speaking to dairy cattle has been shown to increase high-frequency heart charge per unit variability [44]. Like effects have been found in foals, adult horses, and lambs [45]. Intraspecific social licking is very common in cattle, a behaviour considered to exist an expression of positive emotions in cattle [46]. Using these indicators of welfare, we can make inferences about how an animal'due south experiences have changed over time.

It is of import to assess the experiences of an animal as considerately every bit possible in order to make informed decisions nigh the fauna'due south welfare. There are many technologies and practices that claim to upshot in positive welfare, but without physiological and behavioural evidence from the animal, we take no fashion of knowing whether these claims are valid, and we cannot compare these technologies and practices. Animal welfare science has provided an prove base of operations for assessing beast welfare, including the use of multiple indicators of physiology and behaviour, but the relative importance of these indicators has withal to be defined [47,48,49]. What is generally best-selling is that assessing but ane indicator of brute welfare is unlikely to provide a consummate understanding of the creature's experiences [3,49,fifty].

It also important to acknowledge that an improvement to one aspect of an animal's welfare may sometimes consequence in compromised welfare in another attribute. A pertinent example of this is feather pecking in laying hens, which is a major negative welfare situation [51,52,53,54]. Plumage pecking can outcome in pain and threats to pecked birds and can result in decreased feed conversion, leading to poor feathering [53]. Furthermore, if the plumage pecking develops into cannibalism, it tin lead to mortalities every bit high a 25–30% of the flock [51,53]. The awarding of bill trimming tin reduce plumage pecking, with savings of up to AUD 240,000 (USD 185,000) for a flock of 100,000 birds. However, beak trimming itself presents as a controversial welfare issue [51,52,54]. In such cases, where there are trade-offs between different aspects of welfare, the objective assessment of animal welfare becomes even more important in informing management decisions.

Out of all the benefits of improving farm animal welfare, the benefits to the animate being are possibly the near difficult to assess. Where there is high incertitude around the benefits to the animal'southward welfare, objective cess of welfare using multiple physiological and behavioural indicators could reduce some of this uncertainty, making the decision of which infrastructure and management practices to change more straightforward.

4.two. Benefits to the Business concern

The most readily assessed benefits of improving farm animal welfare are the benefits to the business organisation, which take the grade of tangible gains in productivity or of competitive advantage and market place premiums. It is often taken for granted that improving farm animal welfare will ameliorate productivity of the animals. In that location are numerous examples in the literature of positive correlations betwixt farm animate being welfare and diverse measures of productivity (e.yard., weight gain and reproduction) [35,55,56,57,58], but often the benefits of improving welfare are non expressed in economic terms. Furthermore, not all improvements to farm beast welfare result in these benefits, and thus beneath we discuss the circumstances nether which the business may benefit.

It is widely acknowledged that poor animate being welfare ofttimes has implications for productivity metrics, such as fertility and body status. This may be considering the adaptive responses that animals utilise to cope with their environments can sometimes contribute to chronic stress and poor physiological and behavioural functioning [ii,iii,4,59,60,61,62]. For example, it is known that prolonged or sustained stress can disrupt reproductive processes in female pigs [63]. Suboptimal physiological and behavioural functioning is thought to accompany negative subjective experiences, such equally hunger, pain, fear, helplessness, frustration, and anger, and these experiences may be associated with lower productivity. For instance, fear of humans in pigs, induced by brief merely regular slaps, hits, or shocks with a battery-operated prodder, has been shown to reduce growth, feed conversion efficiency, and reproduction in comparison with positive treatment, consisting of a pat or stroke [56,57,64,65,66,67,68]. Similarly, frequent merely cursory human contact with meat chickens of an apparent positive nature, such as gentle touching, talking, and offer nutrient from the hand, can improve growth rates, feed conversion, and allowed part in comparing with minimal human contact [69,70,71,72,73,74,75]. Furthermore, information technology has been shown that dairy farms that handle cows in negative or neutral ways produce less milk [76], whereas positive handling of calves has been correlated with college feed conversion efficiency and growth rates [35,77]. A recent comprehensive review conspicuously articulated that there are financial benefits of good creature welfare through, for example, reduced mortality, improved health, improved resistance to disease and reduced medication, and lower chance of zoonoses and animal-borne infections [78]. All of these parameters directly affect the profitability of businesses with subcontract animals under their care.

Farm brute welfare may likewise affect the quality of the end product. Temple Grandin and others accept done extensive inquiry demonstrating that meat quality improves when you reduce stress in cattle at slaughter [79,80,81,82,83,84,85]. Poor beast welfare occurring during ship and lairage can besides result in reduced quality of product [78].

Perceived product quality may too improve with improved subcontract beast welfare, which may generate a competitive reward for the business concern. Although attitude towards farm creature welfare is only i of the predictors of consumer purchasing behaviour, with price, healthiness, and local product being more important for consumers [26,86,87], sales of "welfare-friendly" animal products, such as free-range eggs, have increased in recent years [88,89]. In 1998, Worsley and Skrzypiec found that an "Fauna Welfare" factor (a negative attitude gene that involved a business with the well-existence of animals) accounted for 10% of the variance in red meat consumption by young Australians aged 18 to 32 [90]. Although a direct comparing is non possible, Coleman et. al. (2019) found a like correlation between "welfare ratings" of beef cattle and beef consumption in 2013 (r = 0.29) and 2018 (r = 0.25) [xx]. These results advise that while the amount of variance in consumption accounted for past welfare attitudes has not changed over the by 20 years, the fact that attitudes are becoming more than negative, at least for some industries [20], suggests that public concerns about subcontract creature welfare may brainstorm to affect consumption. If this is the case, those businesses that are able to demonstrate improvements in farm animal welfare could expect to have a market reward, with more than consumers choosing their products.

The extent to which consumer attitudes about farm animal welfare translate into toll premiums is highly variable. The possibility of earning a market premium varies by product. For instance, whereas participants, on average, were willing to pay extra for a scoop of humane animal care-labelled ice cream to a higher place the toll of conventional ice cream, there was no such willingness to pay for humane animal intendance-labelled cheese [91]. Willingness to pay may also depend on consumers' knowledge of standard manufacture practices and on how the information virtually animal welfare is presented [92]. For instance, Lusk (2019) constitute that when American consumers were provided with graphics explaining both cage and cage-free systems of egg production, their willingness to pay for cage-free eggs decreased, perhaps because the graphics removed misperceptions that muzzle-free implied free range or small farm [93]. There may besides be a confounding issue of quality, and thus information most standards of creature welfare may be associated with products that nowadays good eating quality [92]. Given these mixed findings on consumer willingness to pay for animal welfare attributes, product-specific market place research that takes into business relationship the perceived production quality, consumer demographics, and the presentation of brute welfare claims is likely needed to verify whether a business can wait a price premium for whatsoever given product.

While ethical arguments exist for businesses to continuously invest in the improvement of farm animal welfare, the benefits to businesses in terms of increased returns from this investment are not necessarily articulate. This is specially truthful when considering any benefits that may come up from improving the standard of animal welfare beyond the minimum legal requirements (Effigy 1). For instance, an animal may be producing optimally, thereby providing maximal fiscal returns, but there may still exist telescopic to increment the welfare state of the animal. In this example, the greatest driver to invest in improving animal welfare may not exist increased productivity but rather increased customs acceptance or market protection for the concern. While these drivers may be sufficiently strong to start the costs of improving certain aspects of farm animal welfare (e.g., those that are of most business organization in the community), for other aspects of farm animal welfare, financial incentives for businesses may be lacking.

Where fiscal incentives for businesses are missing, other stakeholders in animal welfare may have to consider "bridging the gap" past offsetting the costs associated with improving farm animal welfare beyond the current limits of profitability. I example of an alternative model to financing improvements in animal welfare is a trend that started in Germany in 2015, whereby pig and poultry farmers began to cooperate with retailers to develop welfare schemes that would pay farmers an actress allowance for welfare-friendly production [94]. The scheme, called Initiative Tierwohl, supports farmers financially in implementing measures for the welfare of their livestock that become beyond the legal standards. Currently, 70% of craven and turkey and 31% of pork produced in Germany is produced under the Initiative Tierwohl standards of brute welfare [95]. This initiative underscores the of import role that retailers can play in providing farmers with the financial means and incentives for improvements to farm animal welfare.

4.3. Benefits to Society

In areas of farm fauna welfare that are of ethical concern to the community, there may be societal benefits to improving farm fauna welfare, even when there is no clear benefit to businesses. For instance, improving the welfare of subcontract animals may result in social benefits, such as creating jobs and sustaining industries in rural areas. Certain individuals may benefit psychologically from more positive interactions with animals. For instance, interviews of several hundred stockpeople in the hog and dairy industries in Australia revealed that the bulk of stockpeople (86% and 76% of hog and dairy stockpeople, respectively) enjoyed working with the animals under their care [96]. Therefore, there may be societal benefits associated with improving the quality of man–animal interactions and with the cognition that the farm animals in one'southward lodge are being treated well. Conversely, improved welfare standards may also result in a societal cost due to negative impacts on small businesses. For example, when the European Spousal relationship banned the use of individual sow stalls in pork production in 2013, many small, family-owned pig farms in Europe were unable to brand the substantial investment required to alter conventional housing systems for pigs and went out of business, leaving a smaller number of larger-scale industrial pork producers [97,98]. Where the potential benefits to society are expected to outweigh the costs, there may be an incentive for government and community organisations to back up businesses to undertake changes that will improve the welfare of subcontract animals.

On a national level, the welfare of farm animals is one of many factors determining a nation's reputation in the international community. For example, i organisation, World Animal Protection, has developed an Animal Protection Index, which assigns rankings to countries according to their legislation and policy commitments to protecting animals [99]. Other benchmarking systems for cross-land comparison in brute welfare have recently been proposed [100]. Although it is unclear whether policymakers currently rely on benchmarking tools to inform policy and trade decisions, the emergence of cross-land comparisons indicates that animal welfare is a growing component of national reputation. Therefore, there may be an argument for governments to support businesses in improving the welfare of farmed animals when there are no clear fiscal incentives for the businesses to practice so.

The value placed on farm fauna welfare by multiple members of society underscores the notion that animate being welfare is a public good, and accordingly, the responsibility for improving information technology is i that is shared past all of club. Whereas in the by there take been cases of adversarial interactions between the businesses that farm animals and sure facets of the community, going forward information technology would seem advantageous to bring all stakeholders to the same tabular array around their shared interest in and responsibility for improving the welfare of farm animals [101]. As mentioned in the discussion on social licence, some businesses have become aware of the demand to engage with the community in explaining their practices on the one hand and responding to public concerns on the other. This will necessarily involve a transition abroad from defensiveness and a greater emphasis on date and transparency. It will too entail a willingness to treat dialogue with members of the public every bit a constructive exercise for all parties involved rather than a method of appeasing or educating the public. Some spaces are beingness created for this constructive dialogue to occur. For example, in Australia, The Beast Welfare Collaborative (TAWC) has created a forum for members of the public, community groups, manufacture bodies, animal protection organisations, companies, bookish institutions, and government agencies to engage constructively around ways to improve brute welfare [102]. EUWelNet is a similar model to TAWC in Europe [101,103], and the Global Coalition for Animal Welfare is an example of an industry-led collaborative initiative in animal welfare [104]. Other participatory initiatives will likely emerge in the future if interest in civic participation continues to abound.

Another potential benefit of proactive engagement with the community is that it could remove some of the uncertainty from the decisions faced by people with animals under their care. Proactive engagement could requite businesses a ameliorate idea of where market incentives be, and where they do non exist, businesses could ask other institutions, such as government and community organisations, to back up their activities to improve subcontract fauna welfare. Where at that place are customs concerns well-nigh specific aspects of farm animal welfare, community members could work directly with the people with animals under their care to understand these aspects in greater detail and collectively develop novel solutions. Evolving upstanding underpinnings of animal welfare in order and scientific understanding of animal cognition will inevitably lead to continuous revision of the means in which guild would like animals to be treated, simply as long as open up and effective dialogue is maintained, businesses and people with animals nether their care should have enough information to adapt to these changes.

5. Making Evidence-Based Decisions most Farm Animal Welfare

Equally demonstrated in this review, there are many factors to consider when making decisions most improvements to subcontract animate being welfare, and the optimal course of action is not ever articulate to the decision maker. Figure two is a determination tool to assist those businesses facing the dilemma of which practices to change in guild to improve farm animal welfare without adversely affecting their profitability.

In the upper-right quadrant of Effigy 2 are practice changes that do good both the welfare of the animal and the business. As long as the changes in practice are based on scientific testify and see societal expectations, nosotros expect that those practices that result in more positive beast welfare states will also take a more than positive issue on the business in terms of profitability and sustainability. Where there is not yet sufficient market demand for changes in practice that positively impact the welfare of animals, there may be bereft incentives for businesses to carry out these changes, every bit depicted in the lower-correct quadrant. Businesses that bear out these changes in practice before the market is fix may in fact lose coin in the short term. Therefore, those who wish to encourage these changes in exercise should focus on creating a market need for them or supporting them through other ways. Similarly, it is plausible that major changes in animal husbandry systems could be positive for fauna welfare, as indicated by scientific prove, only upshot in unprofitable systems of animal production. In this instance, if society is in favour of such systems, the fauna husbandry systems would take to be subsidised in club for the business to be profitable. In the upper-left quadrant are exercise changes that result in higher productivity from the animals and therefore increased profitability for the business but produce negative animal welfare states. These practices are likely unsustainable in the long term due to cumulative negative furnishings on the health and welfare of the animals and to rising societal expectations for brute welfare. Changes in practice that are not based on scientific evidence (i.e., unsubstantiated practices that are perceived to improve animate being welfare) are unlikely to have a lasting positive effect on the business organization, given the lack of evidence underpinning them, and may take a neutral or negative result on the welfare of the animal. In the bottom-left quadrant are those practices which are known to have negative effects on beast welfare, as indicated past scientific evidence, and are likely to result in losses for the business, either in the short term due to reduced productivity of the brute or in the long term due to loss of market.

The importance of engaging with society is a key finding that emerged from our review of the costs and benefits of improving farm animal welfare. On the horizontal centrality of Figure 2, we demonstrate that doing nothing to improve farm brute welfare will likely result in losses for the business organisation due to a widening misalignment of the concern with societal expectations around animal welfare over time. Marketing and public instruction around animal husbandry practices may better returns for the business in the short term, simply because these activities are unidirectional (i.e., they practise not permit for societal input), they are unlikely to provide lasting benefits to the business concern due to the problem of misalignment of expectations just mentioned. Transparency (eastward.thou., a "glass wall" approach) can let for more societal trust than marketing and education practise [105], and some European retailers have begun to pursue transparency effectually farm animal welfare. For instance, in its delivery to the 2026 European Chicken Commitment, Dutch supermarket Albert Heijn has turned to DNA testing to verify its pledge to use only ho-hum-growth breeds of broiler chicken [106]. An ideal approach would be to combine transparency effectually brute welfare with a safe channel for businesses and other members of society to engage in constructive dialogue around best practices in fauna husbandry based on current science. This dialogue would enable those with farm animals under their care and order to piece of work together to develop strategies that ensure that the welfare of farm animals is as proficient equally it maybe tin exist and is continuously improving.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.N.F., P.H.H., 1000.J.C. and A.J.T.; writing—original typhoon preparation, J.N.F., P.H.H., G.J.C. and A.J.T.; writing—review and editing, J.N.F., P.H.H., Thousand.J.C. and A.J.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This enquiry received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicative.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Information Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicative to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the administrative support staff from their respective universities.

Conflicts of Interest

J.North.F. and A.J.T. have been involved with the establishment of The Animal Welfare Collaborative. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Brambell, F.W.R.; Barbour, D.South.; Barnett, M.B.; Ewer, T.K.; Hobson, A.; Pitchforth, H.; Smith, Due west.R.; Thorpe, Due west.H.; Winship, F.J.Westward. Study of the Technical Commission to Inquire into the Welfare of Animals Kept Nether Intensive Husbandry Systems; Her Majesty's Stationary Function: London, UK, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Hemsworth, P.H.; Mellor, D.; Cronin, G.; Tilbrook, A. Scientific assessment of animal welfare. N. Z. Vet. J. 2015, 63, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilbrook, A.; Ralph, C. Hormones, stress and the welfare of animals. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2018, 58, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellor, D.; Patterson-Kane, E.; Stafford, Grand.J. The Sciences of Brute Welfare; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- World System for Animal Health. Introduction to the Recommendations for Animal Welfare. In Terrestrial Animal Health Lawmaking; OIE: Paris, French republic, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- ANSES. ANSES Proposes a Definition of Brute Welfare and Sets the Foundation for Its Research and Expert Appraisal Work. Available online: https://www.anses.fr/en/content/anses-proposes-definition-animal-welfare-and-sets-foundation-its-enquiry-and-skilful (accessed on xix Jan 2021).

- McInerney, J. Animal Welfare, Economic science and Policy: Report on a Report Undertaken for the Subcontract & Brute Health Economic science Sectionalisation of Defra. 2004. Bachelor online: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20110318142209/http://www.defra.gov.united kingdom/bear witness/economics/foodfarm/reports/documents/animalwelfare.pdf (accessed on xix January 2021).

- European-Commission. Attitudes of EU Citizens towards Beast Welfare; European Commission: Brussels, Kingdom of belgium, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Parbery, P.; Wilkinson, R. Victorians' attitudes to farming. In Department of Surround and Primary Industries; Regime of Victoria: Melbourne, Commonwealth of australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gracia, A. The determinants of the intention to purchase animal welfare-friendly meat products in Espana. Anim. Welf. 2013, 22, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European-Commission. Attitudes of European union Citizens towards Beast Welfare, Report; European Committee: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, 1000. Public animal welfare discussions and outlooks in Australia. Anim. Front. 2018, 8, xiv–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, M.Eastward.; González-Montaña, J.R.; Lomillos, J.Chiliad. Consumers' concerns and perceptions of subcontract creature welfare. Animals 2020, 10, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, P.; Shepheard, Chiliad.; Williams, J. What is meant by the social licence. In Defending the Social Licence of Farming: Problems, Challenges and New Directions for Agriculture; University of New England: New South Wales, Australia, 2011; pp. three–11. [Google Scholar]

- Arnot, C. Protecting our freedom to operate: Earning and maintaining public trust and our social license. In Proceedings of the Southwest Nutrition and Direction Conference, Chandler, AR, USA, 5–7 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gunningham, Due north.; Kagan, R.A.; Thornton, D. Social license and environmental protection: Why businesses go beyond compliance. Law Soc. Inq. 2004, 29, 307–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.; Gill, A.; Ponsford, I. Corporate social responsibility at tourism destinations: Toward a social license to operate. Tour. Rev. Int. 2007, eleven, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, J.O.; Jones, B.; McGreevy, P.D. Social License and animal welfare: Developments from the past decade in Australia. Animals 2020, 10, 2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddish Meat Advisory Council. Meat Manufacture Strategic Programme: MISP 2020, Including Outlook to 2030; Red Meat Informational Council: Barton, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, Thousand.; Hemsworth, Fifty.; Acharya, R. Monitoring Public Attitudes to Livestock Industries and Livestock Welfare. FinalReport APL Project 2018/0014. 2019. Bachelor online: https://www.awstrategy.net/uploads/1/2/3/2/123202832/nawrde_no._2018-0014_final_report.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Coleman, G.; Rohlf, V.; Toukhsati, Due south.; Blache, D. Public attitudes relevant to livestock animal welfare policy. Subcontract. Policy J. 2015, 12, 44–47. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, A.E.; Sneddon, J.; Lee, J.A.; Blache, D. Farmer's response to societal concerns about farm animal welfare: The case of mulesing. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2011, 24, 645–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RSPCA Commonwealth of australia. What is the RSPCA's View on Mulesing and Flystrike Prevention in Sheep? Available online: https://kb.rspca.org.au/knowledge-base/what-is-the-rspcas-view-on-mulesing-and-flystrike-prevention-in-sheep/ (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Brennan, A. Wool Manufacture Striking by Some other Mulesing Boycott. Available online: https://www.abc.internet.au/news/2009-01-06/wool-industry-hit-past-some other-mulesing-boycott/258304 (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Sneddon, J. How the Wool Industry Has Undercut Itself on Mulesing. Bachelor online: https://theconversation.com/how-the-wool-manufacture-has-undercut-itself-on-mulesing-956 (accessed on xix January 2021).

- Coleman, 1000.; Toukhsati, Southward. Consumer Attitudes and Behaviour Relevant to the Red Meat Industry: Final Report to Meat & Livestock Australia; Meat & Livestock Australia: North Sydney, Sydney, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Forster, K.; Jeory, T. Exposed: The Shocking and Filthy Conditions Endured by Supermarket Hens in 'Enriched Cages'. Bachelor online: https://world wide web.contained.co.uk/news/u.k./home-news/enriched-caged-hens-chickens-video-footage-eggs-viva-tesco-asda-morrisons-one-stop-lidl-oaklands-subcontract-ridgeway-enriched-cages-a7374281.html (accessed on 23 Dec 2020).

- Australian Associated Printing. Footage Shows Sheep Alive Consign Horror. Available online: https://www.sbs.com.au/news/footage-shows-sheep-live-export-horror (accessed on nineteen November 2020).

- Rice, M.; Hemsworth, L.Thou.; Hemsworth, P.H.; Coleman, G.J. The impact of a negative media result on public attitudes towards animal welfare in the red meat industry. Animals 2020, 10, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Sydney Morn Herald. No More Sow Stalls, Says Pork Industry. Bachelor online: https://www.smh.com.au/environs/conservation/no-more than-sow-stalls-says-pork-manufacture-20101118-17yon.html#:~:text=The%20Australian%20pork%20industry%20has,have%20long%20claimed%20is%20cruel.&text=At%20the%20Australian%20Pork%20Ltd,voluntary%20phasing%20out%20by%202017 (accessed on 23 Dec 2020).

- Locke, S. Voluntary Sow Stall Phase-Out Borderline Approaches for Final 20 Per Cent. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/rural/2016-12-21/voluntary-sow-stall-phase-out-deadline-approaches/8138450 (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Sullivan, Thou.; Cawdell-Smith, A.; Mader, T.; Gaughan, J. Result of shade area on performance and welfare of brusk-fed feedlot cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 2011, 89, 2911–2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meat & Livestock Australia. Information technology Pays to Have Shade. Available online: https://world wide web.mla.com.au/news-and-events/industry-news/it-pays-to-accept-shade/ (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Hemsworth, P.; Coleman, K.; Barnett, J. Improving the Attitude and Behaviour of Stockpersons Towards Pigs and the Consequences on the Behaviour and Reproductive Performance of Commercial Pigs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1994, 39, 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemsworth, P.H.; Coleman, G.J.; Barnett, J.L.; Borg, S.; Dowling, Due south. The effects of cognitive behavioral intervention on the attitude and behavior of stockpersons and the behavior and productivity of commercial dairy cows. J. Anim. Sci. 2002, 80, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman, 1000.J.; Hemsworth, P.H.; Hay, M.; Cox, M. Modifying stockperson attitudes and behaviour towards pigs at a large commercial farm. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2000, 66, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government Department of Agriculture Water and the Environment. Levies Explained. Available online: https://www.agronomics.gov.au/ag-farm-food/levies/publications/levies_explained (accessed on nineteen November 2020).

- Australian Wool Innovation Ltd. Breech Flystrike Strategy 2017/18–2021/22. Available online: https://www.wool.com/globalassets/wool/sheep/inquiry-publications/welfare/flystrike-enquiry-update/gd2689-breech-flystrike-strategy-1718-2122_7_hr.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2020).

- Australian Regime Department of Agriculture H2o and the Environs. Rural Research and Development Corporations. Available online: https://www.agronomics.gov.au/ag-farm-food/innovation/research_and_development_corporations_and_companies#:~:text=The%20RDCs%20are%20funded%20primarily,industry%20gross%20value%20of%20production (accessed on 23 Dec 2020).

- Schmied, C.; Waiblinger, S.; Scharl, T.; Leisch, F.; Boivin, X. Stroking of dissimilar trunk regions by a human: Effects on behaviour and heart rate of dairy cows. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 109, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.; Tarumizu, 1000. Heart rates before, during and later allo-grooming in cattle (Bos taurus). J. Ethol. 1993, 11, 149–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertenshaw, C.; Rowlinson, P.; Edge, H.; Douglas, South.; Shiel, R. The issue of different degrees of 'positive' human–animal interaction during rearing on the welfare and subsequent production of commercial dairy heifers. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 114, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerath, H.S.; Gygax, 50.; Hillmann, Eastward. Are special feed and being brushed judged as positive by calves? Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2014, 156, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, A.; Bauer, L.; Futschik, A.; Waiblinger, S.; Lürzel, S. Talking to cows: Reactions to different auditory stimuli during gentle human-animate being interactions. Forepart. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemsworth, P.; Sherwen, S.; Coleman, G. Man contact. Anim. Welf. 2018, 294–314. [Google Scholar]

- Boissy, A.; Manteuffel, 1000.; Jensen, M.B.; Moe, R.O.; Spruijt, B.; Keeling, L.J.; Winckler, C.; Forkman, B.; Dimitrov, I.; Langbein, J. Assessment of positive emotions in animals to improve their welfare. Physiol. Behav. 2007, 92, 375–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraser, D. Understanding animal welfare. Acta Vet. Scand. 2008, 50, i–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandøe, P.; Corr, Southward.A.; Lund, T.B.; Forkman, B. Aggregating beast welfare indicators: Tin can it be done in a transparent and ethically robust style? Anim. Welf. 2019, 28, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, C.; Caplen, G.; Edgar, J.; Richards, G.; Browne, W. Relationships between multiple welfare indicators measured in private chickens beyond dissimilar time periods and environments. Anim. Welf. 2011, 20, 133–143. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, G.; Mendl, M. Why is there no unproblematic way of measuring animal welfare? Anim. Welf. 1993, 2, 301–319. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin, G.Thou.; Rault, J.Fifty.; Glatz, P.C. Lessons learned from past experience with intensive livestock direction systems. Rev. Sci. Tech. Oie 2014, 33, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glatz, P.C. Neb trimming methods—Review. Asian Austral. J. Anim. 2000, 13, 1619–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glatz, P.C. Effect of poor feather encompass on feed intake and production of aged laying hens. Asian Austral. J. Anim. 2001, 14, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, Y.J.; Glatz, P.C. Application of near infrared spectroscopy (NIR) for monitoring the quality of milk, cheese, meat and fish. Asian Austral. J. Anim. 2000, 13, 1017–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, J.; Hemsworth, P.; Hennessy, D.; McCallum, T.; Newman, E. The effects of modifying the amount of human contact on behavioural, physiological and production responses of laying hens. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1994, 41, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonyou, H.; Hemsworth, P.; Barnett, J. Furnishings of frequent interactions with humans on growing pigs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1986, 16, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemsworth, P.; Barnett, J.; Hansen, C. The influence of treatment past humans on the behavior, growth, and corticosteroids in the juvenile female grunter. Horm. Behav. 1981, 15, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemsworth, P.; Barnett, J.; Hansen, C. The influence of inconsistent handling by humans on the behaviour, growth and corticosteroids of young pigs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1987, 17, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broom, D.M.; Johnson, K.M.; Broom, D.Thousand. Stress and Animate being Welfare; Springer: Berlin, Deutschland, 1993; Book 993. [Google Scholar]

- Moberg, 1000.P. Biological response to stress: Implications for animal welfare. In The Biology of Animal Stress: Basic Principles and Implications for Animal Welfare; Moberg, Grand.P., Mench, J., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2000; Volume 1, p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Sapolsky, R.Thousand. Endocrinology of the stress-response. In Behavioral Endocrinology, 2d ed.; Becker, J.B., Breedlove, Due south.M., Crews, D., McCarthy, Thou.M., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 408–450. [Google Scholar]

- Hemsworth, P.H.; Rice, M.; Karlen, Grand.Yard.; Calleja, L.; Barnett, J.L.; Nash, J.; Coleman, G.J. Man–creature interactions at abattoirs: Relationships between treatment and animal stress in sheep and cattle. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2011, 135, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A.I.; Hemsworth, P.H.; Tilbrook, A.J. Susceptibility of reproduction in female pigs to damage by stress or summit of cortisol. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2005, 29, 398–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemsworth, P. Human being–fauna interactions. In Welfare of the Laying Hen; CABI: Wallingford, United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland, 1987; p. 329. [Google Scholar]

- Hemsworth, P.; Barnett, J.; Hansen, C. The influence of handling past humans on the behaviour, reproduction and corticosteroids of male person and female pigs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1986, 15, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemsworth, P.; Price, E.; Borgwardt, R. Behavioural responses of domestic pigs and cattle to humans and novel stimuli. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1996, 50, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemsworth, P.; Barnett, J. The effects of aversively handling pigs, either individually or in groups, on their behaviour, growth and corticosteroids. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1991, 30, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabrook, M.F.; Bartle, N.C. The practical implications of animals responses to man (specifically effects on product parameters). Proc. Br. Soc. Anim. Prod. 1972, 1992, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, W.; Siegel, P. Adaptation of chickens to their handler, and experimental results. Avian Dis. 1979, 23, 708–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, W.; Siegel, P. Effects of early ecology stresses on chicken trunk weight, antibody response to RBC antigens, feed efficiency, and response to fasting. Avian Dis. 1980, 24, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, West.; Siegel, P. Influences of sequences of environmental factors on the response of chickens to fasting and to Staphylococcus aureus infection. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1982, 43, 137–139. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gross, W.; Siegel, P. Some effects of feeding deoxycorticosterone to chickens. Poult. Sci. 1981, sixty, 2232–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, J.; Siegel, P. Homo handling, flock size and responses to an E. coli claiming in immature chickens. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1987, nineteen, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulkifli, I.; Gilbert, J.; Liew, P.; Ginsos, J. The furnishings of regular visual contact with human beings on fearfulness, stress, antibody and growth responses in broiler chickens. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2002, 79, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulkifli, I.; Azah, A.S.N. Fearfulness and stress reactions, and the performance of commercial broiler chickens subjected to regular pleasant and unpleasant contacts with human beingness. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2004, 88, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waiblinger, Due south.; Menke, C.; Coleman, G. The relationship betwixt attitudes, personal characteristics and behaviour of stockpeople and subsequent behaviour and production of dairy cows. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2002, 79, 195–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lensink, J.; Boissy, A.; Veissier, I. The relationship between farmers' mental attitude and behaviour towards calves, and productivity of veal units. Ann. Zootech. 2000, 49, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawkins, M.S. Creature welfare and efficient farming: Is conflict inevitable? Anim. Prod. Sci. 2017, 57, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandin, T. The effect of stress on livestock and meat quality prior to and during slaughter. Int. J. Written report Anim. Probl. 1980, 1, 313–337. [Google Scholar]

- Grandin, T. Euthanasia and slaughter of livestock. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1994, 204, 1354. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Grandin, T. Handling methods and facilities to reduce stress on cattle. Vet. Clin. North. Am. Food Anim. Pract. 1998, 14, 325–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandin, T. Livestock-treatment quality assurance. J. Anim. Sci. 2001, 79, E239–E248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandin, T. Fauna welfare and food safety at the slaughter constitute. In Improving the Safety of Fresh Meat; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 244–258. [Google Scholar]

- Grandin, T. Auditing brute welfare at slaughter plants. Meat Sci. 2010, 86, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velarde, A.; Fàbrega, E.; Blanco-Penedo, I.; Dalmau, A. Animal welfare towards sustainability in pork meat product. Meat Sci. 2015, 109, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, W.; Viaene, J. Beliefs, mental attitude and behaviour towards fresh meat consumption in Kingdom of belgium: Empirical evidence from a consumer survey. Nutrient Qual. Adopt. 1999, x, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, Chiliad.; Hay, M.; Toukhsati, S. Effects of consumer attitudes and behaviour on the egg and pork industries. In Written report to Australian Pork Ltd and Australian Egg Corporation Ltd; Monash University: Melbourne, Austrilia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bray, H.J.; Ankeny, R.A. Happy chickens lay tastier eggs: Motivations for ownership gratuitous-range eggs in Commonwealth of australia. Anthrozoös 2017, 30, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondoni, A.; Asioli, D.; Millan, E. Consumer behaviour, perceptions, and preferences towards eggs: A review of the literature and give-and-take of industry implications. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 106, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worsley, A.; Skrzypiec, G. Practise attitudes predict reddish meat consumption amidst young people? Ecol. Nutrient Nutr. 1998, 37, 163–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbakidze, Fifty.; Nayga, R.M., Jr. The furnishings of information on willingness to pay for animal welfare in dairy production: Application of nonhypothetical valuation mechanisms. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95, 1099–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napolitano, F.; Pacelli, C.; Girolami, A.; Braghieri, A. Effect of information about animal welfare on consumer willingness to pay for yogurt. J. Dairy Sci. 2008, 91, 910–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lusk, J.L. Consumer preferences for cage-free eggs and impacts of retailer pledges. Agribusiness 2019, 35, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heise, H.; Overbeck, C.; Theuvsen, Fifty. The initiative tierwohl (animal welfare initiative) from the perspective of diverse stakeholders: Assessments, opportunities for comeback and future developments. Ber. über Landwirtsch. 2017, 95, one–35. [Google Scholar]

- Initiative Tierwohl. Available online: https://initiative-tierwohl.de/ (accessed on xix Jan 2021).

- Hemsworth, P.; Coleman, K. Human-livestock interactions: The stockperson and the productivity and welfare of intensively farmed animals. In Human-Animal Interactions and Fauna Productivity and Welfare; Hemsworth, P., Coleman, G., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2011; pp. 47–83. [Google Scholar]

- Augère-Granier, M.-L. The EU Squealer Meat Sector. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2020/652044/EPRS_BRI(2020)652044_EN.pdf (accessed on nineteen Jan 2021).

- Linden, J. Market Bear on of EU Regulations on Group Housing of Sows. Bachelor online: https://world wide web.thepigsite.com/articles/marketplace-affect-of-eu-regulations-on-group-housing-of-sows (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Earth Creature Protection. Animal Protection Index. Bachelor online: https://api.worldanimalprotection.org/ (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Sandøe, P.; Hansen, H.O.; Rhode, H.L.H.; Houe, H.; Palmer, C.; Forkman, B.; Christensen, T. Benchmarking subcontract creature welfare—A novel tool for cross-country comparison applied to sus scrofa production and pork consumption. Animals 2020, x, 955. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, J.; Blache, D.; Maloney, Southward.K.; Martin, Thousand.B.; Venus, B.; Walker, F.R.; Head, B.; Tilbrook, A. Addressing fauna welfare through collaborative stakeholder networks. Agronomics 2019, nine, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Animal Welfare Collaborative. Available online: https://theanimalwelfarecollaborative.org/ (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Veissier, I.; Spinka, One thousand.; Bock, B.; Manteca, X.; Blokhuis, H. Executive Summary of the Project Coordinated European Brute Welfare Network (EUWelNet). Bachelor online: http://www.euwelnet.european union/media/1189/excecutive_summary_final.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- The Global Coalition for Creature Welfare. Available online: http://www.gc-animalwelfare.org/ (accessed on nineteen January 2021).

- Due north American Meat Institute. Meat Found Releases New Temple Grandin-Narrated 'Glass Walls' Video of Lamb Processing Plant. Available online: https://world wide web.meatinstitute.org/index.php?ht=d/ArticleDetails/i/121711 (accessed on 23 Dec 2020).

- Askew, K. Meat Transparency: The Answer Could Be in the Deoxyribonucleic acid. Available online: https://www.foodnavigator.com/Commodity/2020/10/08/Meat-transparency-The-reply-could-be-in-the-Deoxyribonucleic acid# (accessed on 19 January 2021).

Figure one. Continuum of beast welfare. The state of an animal'south welfare tin vary from negative to positive. While these terms may exist considered subjective, with the potential for meaning to change between people and over time, the principle is that there is a continuum of levels of animal welfare. The cost to ensure that the welfare of animals is not negative may be considered an essential price. The economic advantage from investment to movement the level of animate being welfare to more positive states on the continuum is challenging to evaluate, although market place protection afforded by gaining and maintaining consumer and community support may well justify the costs to ensure positive states of brute welfare.

Figure 1. Continuum of animal welfare. The country of an animal's welfare tin vary from negative to positive. While these terms may exist considered subjective, with the potential for significant to alter between people and over fourth dimension, the principle is that there is a continuum of levels of beast welfare. The cost to ensure that the welfare of animals is non negative may be considered an essential cost. The economic advantage from investment to move the level of animal welfare to more positive states on the continuum is challenging to evaluate, although market protection afforded by gaining and maintaining consumer and community support may well justify the costs to ensure positive states of animal welfare.

Figure two. Conclusion tool for businesses because changes in practice to better farm fauna welfare. The horizontal axis depicts the effect of the change in exercise on the welfare of the animal, with more than positive furnishings towards the correct. The vertical centrality depicts the upshot of the alter in practice on the profitability of the business, with more than positive furnishings towards the superlative.

Figure 2. Decision tool for businesses considering changes in practise to improve farm animal welfare. The horizontal axis depicts the effect of the change in practice on the welfare of the animal, with more positive effects towards the correct. The vertical axis depicts the issue of the modify in practice on the profitability of the business, with more than positive furnishings towards the top.

| Publisher'due south Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open up access commodity distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC By) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Source: https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0472/11/2/104/htm

Posted by: eldercovis1990.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Does Farm Animal Welfare Affect Agriculture .edu"

Post a Comment